- Hymenoplasty recreates the thin vaginal membrane called the hymen.

- This controversial procedure is intended to restore the appearance of virginity.

- Some experts see hymen reconstruction as a manifestation of female subjugation.

- Others view the procedure as acceptable and even necessary or life-saving, in some situations.

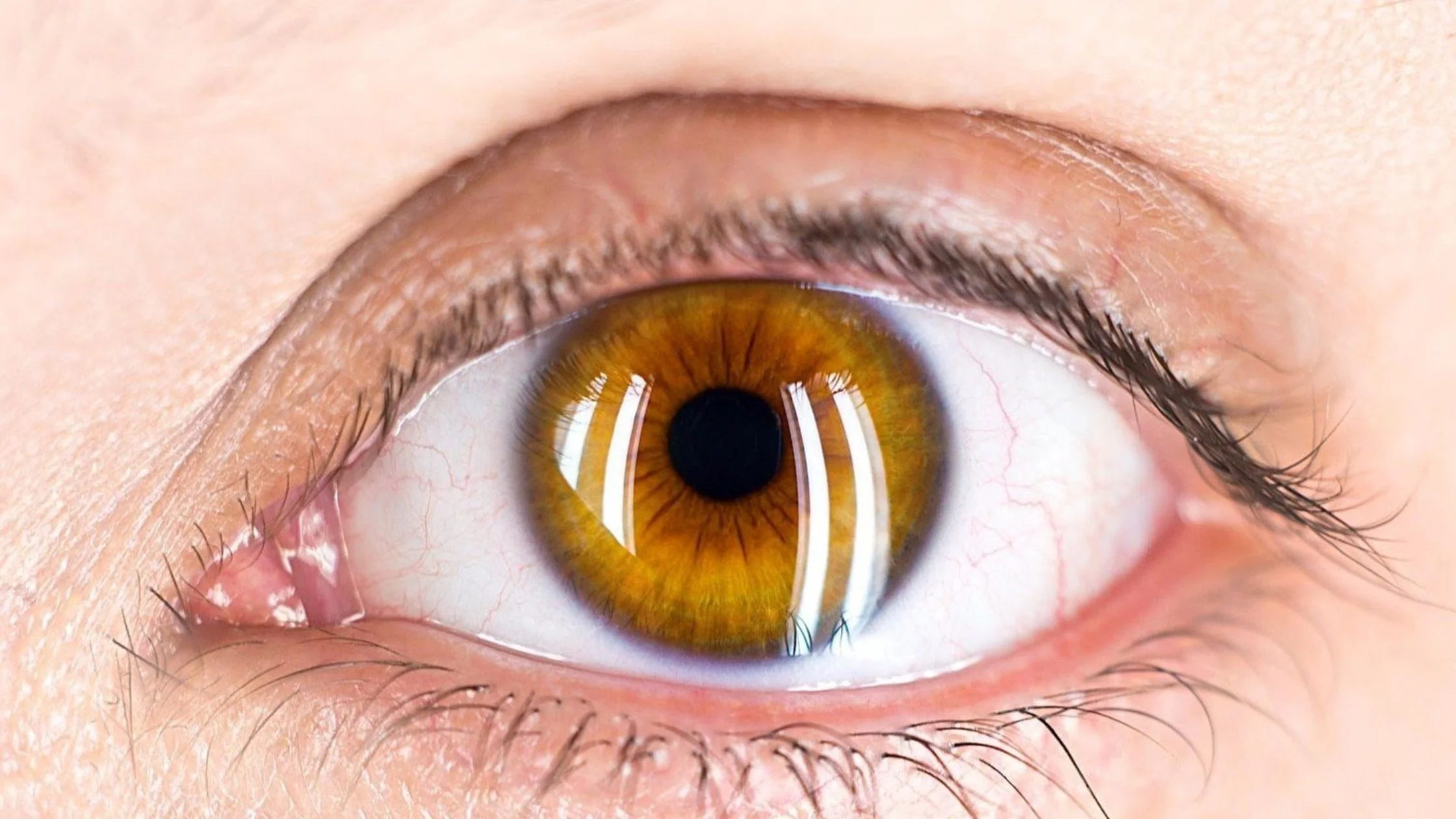

Named for Hymenaeus, the Greek God of marriage, the hymen is a thin vaginal membrane that forms during embryonic development. Its biological significance is unknown. Both the shape and prominence of the hymen varies from woman to woman, with some being born with no hymen at all.

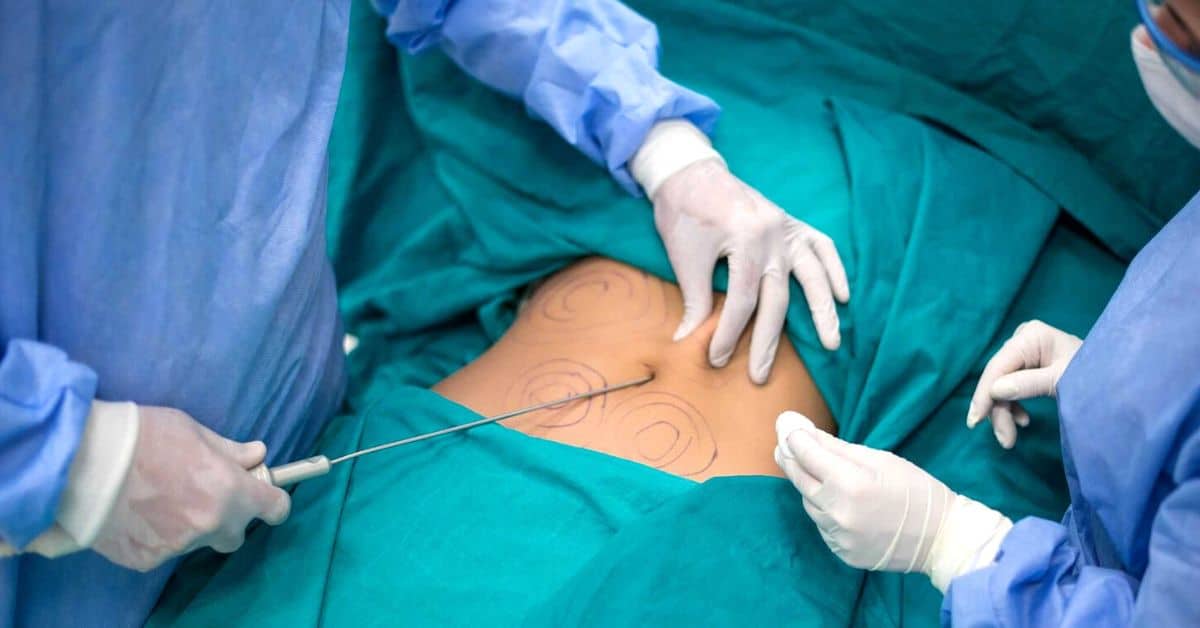

The hymen usually tears at some stage of a girl or woman’s life. Hymen reconstruction surgery is a medical procedure intended to recreate the hymen. During this procedure the tissue that remains after the tear is dissected from the surrounding vaginal wall and sutured back together. It takes approximately six weeks to heal.

Though sexual activity is by no means the only cause of this hymen tearing, it is believed to be by most cultures. Because the membrane is so closely (and falsely) associated with virginity, surgery to restore the hymen is almost always performed to restore the appearance of virginity.

For this and many other reasons relating to culture, religion, human rights, safety and other considerations, hymenoplasty surgery is a subject of some controversy. Is the procedure really necessary? Should it be condemned or even banned? We spoke with experts in different fields to learn more.

What Motivates a Woman to Undergo Hymen Surgery?

Many women who seek out hymen restoration do so for cultural or religious reasons. In some cultures, a broken hymen can prevent a woman from finding a marriage partner, ruin her reputation, or even put her life at risk.

“In many parts of the world, especially in very conservative areas like the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa, there are strict cultural rules around virginity, particularly a woman’s virginity,” says Johanna Higgs, a women’s rights advocate and founder of Project Monma, an organization that aims to raise awareness of the endemic levels of violence and discrimination against women and girls around the world. Higgs has traveled across the globe documenting examples of such violence and discrimination.

In these societies, Higgs explains, a woman’s value is based on her ability to be married and bear children, and it is believed that a woman will only be able to get married if she is a virgin. “The necessity for her to be a virgin is largely based around the man’s desire for her to be one. Most men will not accept a woman who is not a virgin,” she explains.

And because marriage is often tied with social status and wealth in these societies, most families consider a woman’s inability to get married disastrous. Therefore, to these families, ensuring that their daughters remain virgins is considered extremely important.

In other situations, says Higgs, a young couple might require permission from family members to get married, as in the case of arranged marriages. “If family members refuse to permit two young people to marry, the couple might carry on with the relationship anyway, and if it becomes sexual it could cause great problems within the family,” she says. “This might lead the couple to seek out hymen restoration surgery.”

While hymen restoration surgery may be the most invasive method of “restoring virginity,” it’s not the only method. “In Uganda, there is a significant push in several communities to maintain virginity as long as possible,” says Michael Ingber, MD, a board-certified urogynecologist and specialist in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at The Center for Specialized Women’s Health, Division of Garden State Urology. Ingber has traveled to Uganda and seen this firsthand. “There are even ‘tightening’ creams that can be found at local pharmacies, or local healers who provide therapies with herbs to cleanse and rejuvenate the vagina— neither of which actually work.”

In the West

If you think this procedure is reserved to non-Western cultures, think again. The fact is surgeons on several continents — including North America — offer hymenoplasty. Some practices even go so far as to pitch the procedure as a form of female empowerment that can be pursued for personal reasons. “By restoring and repairing the tissue, a woman can regain control and ownership of the area and feel good about her body once again,” says the website of one such practice.

All of this, of course, points to at least some degree of demand for hymen restoration in the West. Virginity may not have the same economic or social ramifications here, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t any women who want to “restore” their virginity.

Tragically, in some cases this may be a result of rape or incest. According to the National Health and Social Life Survey, approximately one third of women say they either didn’t want sex the first time they had it or remember being forced into it through incest, sexual assault, or other coercive or exploitative means.

In other cases no such crimes are involved. For example, some conservative religious traditions still persist in the western world, and it’s not unheard of for women adhering to such traditions to seek out hymen restoration in an attempt to disguise their sexual past from their future husband. This happens in countries like the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.

Nevertheless, although hymenoplasty is offered by a few practices in North America and other Westernized cultures, many physicians and women’s advocates in these regions view hymenoplasty as a manifestation of female subjugation.

Indeed, sometimes it is a matter of life and death. Over the past couple of decades stories of “honor killings” — the horrific practice whereby a male family member murders a female relative to preserve the “honor” of the family — have shocked the world’s conscience. Loss of virginity is often the motivation behind these acts.

And as if these acts weren’t contemptible enough, in cases where a torn hymen is the “evidence” cited to justify the act, the murder victim may in fact still be a virgin. This is because, unbeknownst to many, sex is not the only way the hymen can tear.

“From a medical standpoint, the effect of associating a hymenal tear or bleed with virginity is not compelling,” says Cheri A. Ong, MD, a Scottsdale, AZ based plastic surgeon and passionate advocate for women’s health. “There can be non-sexual reasons why a teenage girl may have a tear. It could have resulted from sporting activities or inserting tampons or something she may not even be aware of. There are women with wide or elastic hymens, where no tears have occurred despite sexual intercourse. Also, some women are born without a hymen.”

But because a woman’s safety or well-being is often involved in her decision to seek out hymenoplasty, even experts who deplore the subjugation that often motivates these women can see some justification for the procedure. This includes Ong. It’s a tough and dangerous situation to be involved in, she says, but performing the procedure could potentially save a life. “In extreme societies, the male relatives would want to know why she didn’t bleed during intercourse and arrange for a male relative to carry out an honor killing. If you had the opportunity to prevent a life lost, wouldn’t you do it?”

Another Viewpoint

Other physicians simply have no problems with the procedure. “I respect different cultures and understand the social issues related to wanting to be a virgin at marriage,” says Ingber. “While I personally would never want this for my daughter or any family member, I understand the desire for some.”

In fact, Ingber performs hymenoplasty for certain patients at his New Jersey practice. He says the procedure isn’t generally covered by insurance and may cost between $2,500 and $10,000, depending on the geographic location where the procedure is done and how much work is required.

Sometimes, however, a portion of the procedure—primarily the anesthesia/facility fees—may be covered if it’s considered medically necessary. He cites concomitant vaginal prolapse (hernia) and incontinence as examples of conditions that may render part of the procedure medically necessary.

In addition to hymenoplasty, Ingber offers alternative procedures to tighten the opening of the vagina for women who, as he puts it, “are bothered by feeling too lax (loose).” These include a surgical procedure called perineorrhaphy as well as a therapy which uses radiofrequency energy to tighten the vaginal opening.

While some physicians and other members of society view such procedures in a negative light, Ingber regards them as part of a delicate balancing act physicians need to carry out. “As physicians we must respect cultural desires but at the same time do no harm.”