What is the first word that comes to mind when you think of plastic surgery? We’d be willing to bet that it’s not “children.” But then again, you probably weren’t thinking of congenital deformities, either.

Each year, approximately 3 percent of all children born in the U.S. have a major malformation at birth, according to the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Many of these deformities can be effectively treated through surgery. What many people don’t realize is that the surgeons performing these surgeries are the same plastic surgeons performing facelifts and nose jobs. During their fellowship training, most plastic surgeons are trained not only in cosmetic surgery but also in reconstructive surgery. As a result, when it comes to helping people with congenital deformities, plastic surgeons are on the front lines.

Usually, they are one component of a multi-specialty team. Many cases, especially complex ones, require coordination between a facial plastic surgeon and several other types of professionals, possibly including a dentist, a speech pathologist, a nutritionist and others.

We spoke to three plastic surgeons about this important aspect of their work.

Congenital Deformities Treated by Plastic Surgeons

Plastic surgeons are called in to help with a variety of congenital deformities. The most common include soft tissue problems such as cleft lip and cleft palate, vascular formations, ear abnormalities, and deformities of the facial bones and/or skull.

Other disorders and deformities treated by plastic surgeons include:

- Severe skeletal issues such as craniosynostosis, a congenital deformity whereby one or more of the fibrous joints between the bones of a baby’s skull (cranial sutures) close prematurely, before the baby’s brain has fully formed

- Skin lesions

- Hand and limb deformities

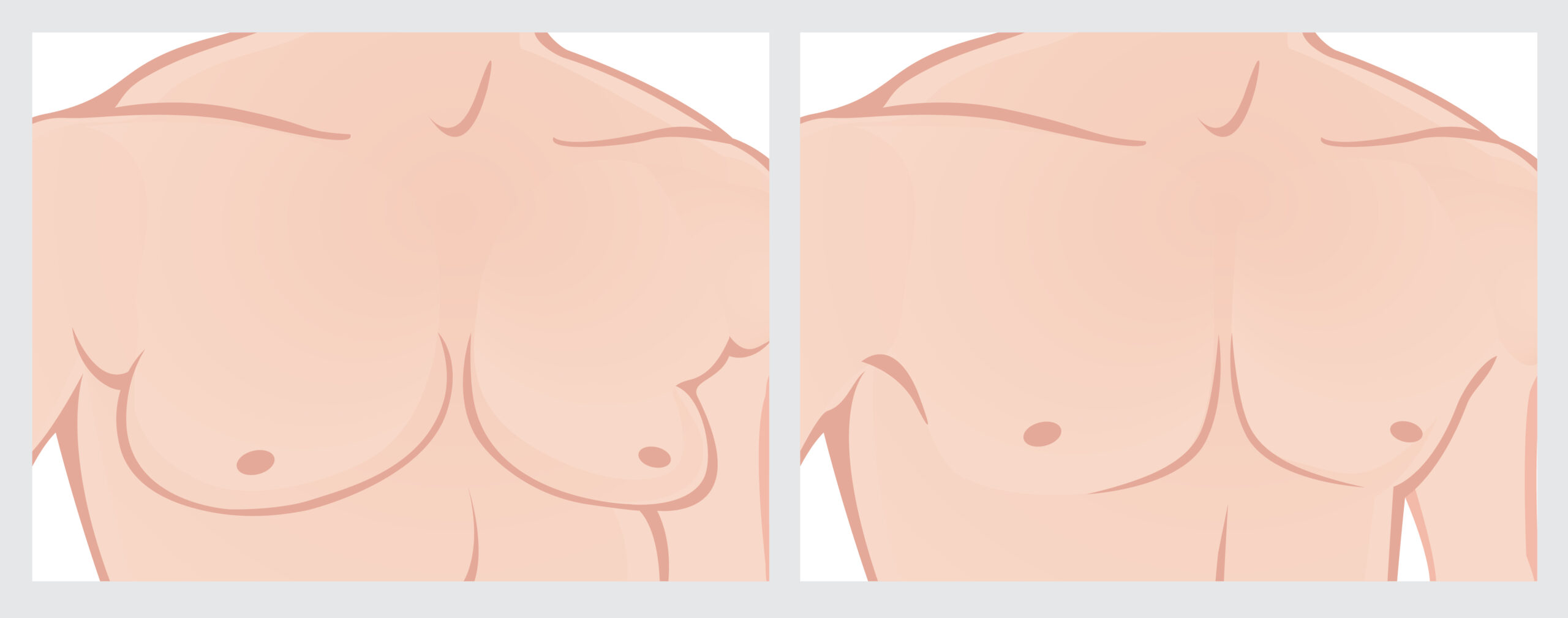

- Breast deformities

- Hemifacial macrosomia (a condition in which the lower half of a baby’s face is not fully developed and does not grow normally)

- Nasal deformities

- Treacher Collins Syndrome (a condition characterized by underdeveloped bones and tissues)

- Congenital facial paralysis

- Jaw abnormalities

- Facial asymmetries

At What Age Are These Deformities Treated?

Most congenital deformities are treated during childhood, some as early as one month after birth. For example, at the world-renowned Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, cleft lip cases are usually repaired at around 3 months of age, and cleft palates are addressed at about 9-12 months of age, according to Patrick J. Byrne, MD, FACS, MBA, Professor and Director of the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the School of Medicine and member of the Board of Directors at the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS).

This is particularly true if the deformity is interfering with function.

“An underlying principle of treating these deformities that affect form and function is that if the deformity is known or anticipated to interfere with a child’s function, physical development, or social development, the deformities as a matter of principle are usually taken care of at a very young age,” says Fred G. Fedok, MD, FACS, President of AAFPRS. “As an example a cleft lip deformity, which will affect the ability of a child to effectively suck for feeding will need treatment in the first weeks and months of life.”

But it is not uncommon for plastic surgeons to continue working with these same patients into adulthood. One common example is the nasal deformity associated with cleft lip, which is typically addressed through a rhinoplasty procedure during a patient’s teenage years.

Skin lesions, ear deformities and small vascular malformations are usually treated later in life or may even be left alone. This is because plastic surgeons like to have the input of the patient once he or she has reached a mature age. Long-lasting scars and incomplete reconstructions also may be addressed once the patient is an adult.

What Are the Challenges?

Plastic surgeons are often faced with significant challenges when correcting congenital deformities. “Treating children is both rewarding and challenging,” says Andrew Tussler, MD, an Austin plastic surgeon who is board certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery. “Even the simplest procedures usually require some element of general anesthesia. It is difficult to care for wounds and stitches so all care must be planned out ahead of time so a plan is presented to the family.”

Tussler adds that keeping the family informed can be daunting because it requires adequate time and a simple language when explaining procedures. Trust is paramount – surgeons must attempt to avoid uncomfortable procedures to the extent possible and try to prevent parents from associating the surgeon with any discomfort that does occur.

There is also the fact that some of deformities can have a profound impact on the patient’s development, growth and even brain development. Both form and function are directly tied to this. As Byrne explains it, performing surgery to correct congenital deformities requires an understanding not just of 3 dimensions, but 4. “Our operations can affect how the patient’s anatomy develops and grows,” he says. “For example, scarring from palate surgery can prevent normal growth and development of the upper jaw.”

The extent and timing of the surgery must take into account the ultimate goal of providing as much normalcy as possible over the course of the child’s lifetime. And this requires considerable understanding, judgement, and experience. This is why fixing congenital deformities often requires a multi-specialty team, not just a plastic surgeon.

“Depending on the complexity of the issue, appropriate management will depend on coordination with several professional fields,” says Fedok. “For instance, the most appropriate management of the patient with cleft lip and palate deformity usually requires the coordination of care between at least the facial surgeon, a speech pathologist, a nutritionist, as well as dental personnel.”

The Good News: Many Recent Advances

The good news is that enormous progress has been made over the years. Fedok cites advances in laser technology, which have revolutionized the management of patients with relatively minor deformities such as vascular malformations, and advances in pediatric anesthesiology as well as imaging and computer modeling for complicated issues like craniosynostosis.

Tussler points out that ear molding within the first weeks has become more common. Absorbable materials for craniofacial surgery have eliminated the need for metallic plates, and distraction devices which help move bones in the jaw are helping surgeons avoid the need for tracheostomy procedures (in which an incision is made in the windpipe to relieve a breathing obstruction). Furthermore, medicines like Propranolol have been found to be effective in stopping the growth of hemangiomas and limiting the number of surgeries needed to treat them.

Last but not least are the more futuristic-sounding innovations such as tissue engineering and 3D printing, which may soon have a meaningful impact on treatments for congenital deformities, according to Byrne, who recently touched on these developments as well as likely innovations on the horizon in an article published in the Wall Street Journal.

Tips from the Experts

If you or your child was born with a congenital deformity, you are undoubtedly anxious to find the best treatment possible. Here are some things to keep in mind from our experts:

Fedok: Always seek out the best consultation possible in your general locale. Frequently the physicians you see for other reasons will be a good source of referral to competent physicians in your area. You can seek advice through the AAFPRS and the other professional societies. Have all your questions answered satisfactorily. Sometimes more than one consultation is necessary.

Byrne: Keep in mind what matters is the CHILD’S wellbeing. I say this because I see well-intentioned parents err in both directions. I see kids who really do NOT have any significant deformity, and their parents push them to improve their appearance with nasal surgery, chin surgery, etc. This is really tragic, and I think folks would be surprised at how common this is. On the other end of the spectrum, we occasionally see mothers and fathers whose children have real deformities – but mom and dad don’t see it this way, and are against surgery that could really dramatically improve their child’s life experience. Either extreme is a distortion of the parents’ true role: to assist supporting their child’s wellbeing. It’s about them!

Tussler: Kids are not just small adults, and the approach to treatment requires significant empathy for [how] the child interprets their deformity and their relationship with the plastic surgeon. Care for the family and bonds between parent and child are other factors a good surgeon will take into consideration.

It is also important to note that, unlike elective cosmetic surgeries, surgery to correct congenital deformities is covered by most insurance carriers, particularly when the issue is causing a functional problem. Just to be safe, take detailed photos of you or your child’s deformity and ask your surgeon to write a letter for you.