- Nerve grafts can restore sensation and movement to areas paralyzed by damaged nerves.

- Some grafts, known as allografts, come from voluntary living donors or, more often, cadavers.

- It could take years before a nerve is fully healed, depending on the extent of the damage.

While most traumatic injuries heal over time – with the help of medical treatment, at least – it’s not always easy to mend damage to certain areas of the body.

Nerve damage, for example, can lead to the permanent loss of sensation or movement. It can also change the way we look, prevent us from participating in the activities we love, and often leaves us with chronic pain.

In some instances nerves heal themselves over time. However, there’s no guarantee of this, and many cases of nerve damage require surgical intervention.

There are several ways plastic surgeons can treat nerve damage. They can directly repair damaged nerves by removing the damaged portion and connecting the healthy ends, transplant a healthy functioning nerve from one part of the body to another or perform a nerve graft.

We spoke with Dr. Gregory Still of the Table Mountain Foot and Ankle Clinic in Wheat Ridge, Colorado about nerve transplant and grafting. Dr. Still, a podiatrist and peripheral nerve surgeon, specializes in nerve allografts for the treatment of chronic pain. He offered us his expertise so we might better understand the life-changing potential of this surgery.

What are nerve grafts?

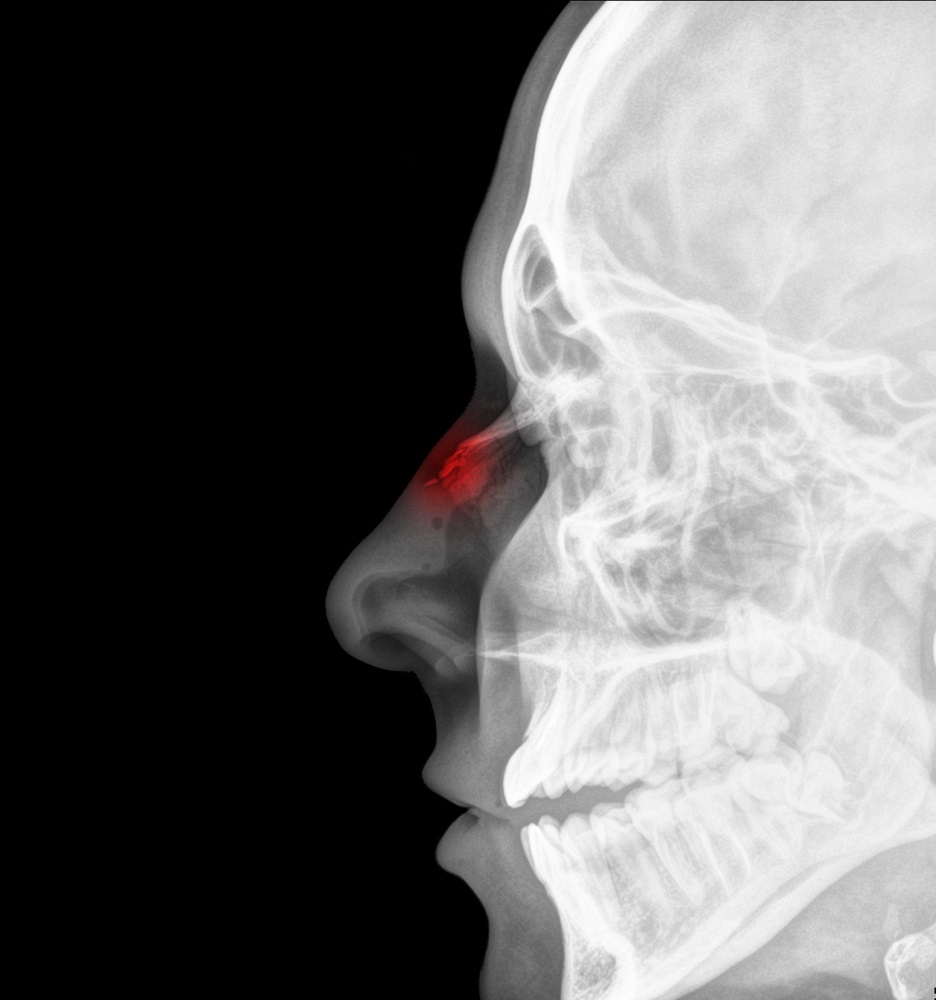

Put simply, a nerve graft is a bridge connecting the healthy ends of a nerve that has been damaged. But before we go too in depth as to what this means, let’s take a moment to review the anatomy of a nerve.

Nerves are structures that transmit information between the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body. They give our brain the power to move our limbs, feel external objects, speak, and even breathe. Think of nerves as large cables acting as an information highway. These cables contain nerve fascicles (bundles of nerve fibers). Individual nerve fibers are known as axons. Exactly how large a nerve is and how many fascicles it contains depends on the nerve in question.

The nervous system is split into two main sections: the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. The former refers strictly to the brain and spinal cord and the latter to the nerves and fibers that connect the body to the central nervous system. For this reason, these nerves are often referred to as peripheral nerves.

Different peripheral nerves perform different functions. The two primary nerve functions address movement (motor nerves) and sensation (sensory nerves). Which type of nerve requires grafting will dictate certain aspects of the procedure.

When one of these nerves gets damaged, the transmission of information is brought to a halt until the nerve is able to regrow. Sometimes this happens naturally, and other times the damaged nerve needs a little help. Nerve damage can also lead to chronic pain. This is also not uncommon when nerves are permanently severed during surgery, as with an amputation.

In most cases, a portion of nerve is removed from another part of the body (or from a donor) and grafted onto the damaged nerve, much like a skin graft. This portion of the nerve acts as a scaffold upon which the damaged nerve can regrow. This nerve graft is not a complete replacement. It simply facilitates the healing process.

In some cases, nerve grafts aren’t intended to restore movement or sensation. Dr. Still frequently treats patients whose chronic pain resulting from surgery or trauma is best mended through what he terms “a nerve graft to nowhere.” Instead of connecting the healthy ends of damaged nerves, he connects the end of the severed nerve to a nerve graft and implants the other end of the graft into muscle, thereby preventing “cauliflower-like” axons from developing into painful neuromas (pinched nerves).

How do nerve grafts work?

We’ll go into more depth about the kind of damage that might necessitate a nerve graft later in this article, but for the moment let’s assume you have a damaged nerve that has been marked for nerve grafting.

First, your surgeon will determine what kind of nerve graft you need. Often, this will be an autologous nerve graft (autograft). In other words, the graft is taken from a donor site on your body and attached to a host site on your body (i.e. the damaged nerve). This graft is sometimes also referred to as an autogenous graft.

In some cases, your surgeon may wish to do an allograft. Allografts are grafts that could come from a direct donor, but many surgeons, including Dr. Still, acquire their cadaveric allografts from AxoGen. AxoGen’s Avance Nerve Grafts are harvested, cleaned, and stored for use by medical professionals. Plus, they’re the only nerve allografts currently approved by the FDA.

Allografts are often used in cases where the damaged nerve is a motor nerve as opposed to a sensory one. Grafts are most successful when taken from nerves of a similar nature to the damaged one. Motor nerve grafts have fewer satisfactory donor site options.

Dr. Still notes that allografts also do away with the added complication of requiring a donor site at all. “It’s like robbing Peter to pay Paul,” he says of removing nerves from one part of the body to mend another. He says that in recent years “the trend has been to move toward allografts” — at least where chronic pain in the lower extremities is concerned.

If your plastic surgeon has decided on an autograft, the next thing to do is choose the donor site. We’ll explore common donor nerves and the factors that play into choosing donor sites later in this article, but for the moment let’s assume your plastic surgeon has found an appropriate location.

Once that has been done your surgeon will first expose the damaged nerve and clear out any damaged material that they find. They will ensure that the nerve ends (nerve stumps) are healthy and therefore be capable of regenerating nerve fibers once the graft is in place. In the case of a “graft to nowhere,” surgeons need only concern themselves with the single nerve end to which the graft will be attached.

For autografts, your plastic surgeon will then expose the donor site and remove a portion of nerve appropriate for treating the damaged area. This may be as simple as removing a solid section of nerve comparable in size to the damaged area, or it may be more complicated. Sometimes nerves need to be removed in sections and attached to form a graft of the necessary size. This is called a cable graft.

The cable graft is attached using sutures so small they need to be applied using a microscope. The sutures attach the graft to either side of the damaged nerve, or, for the “graft to nowhere,” one end is attached to a damaged nerve and the other embedded in the muscle. In cases where there are five or more fascicles in the damaged nerve, these fascicles may be grafted and sutured individually. The wounds are all then closed.

As the site heals, the nerve fibers in the graft dissolve. However, the framework provided by the graft remains and acts as a pathway for new nerve fibers. In this way the nerve heals itself, reconnecting across the graft.

>> Connect with our medical review team to learn more about this complex procedure and how it may pertain to your unique situation.

What is the difference between a nerve graft and a nerve transfer?

Nerve grafts are not to be confused with nerve transfers. Although the two procedures sound very similar and are used to treat the same concerns, they are fundamentally different.

A nerve transfer also harvests nerves with lesser functions and uses those nerves to bridge gaps in the damaged nerves. Except nerve transfers don’t simply graft a framework for new nerve fibers to grow on. They actually transfer whole functioning nerves from one place in the body to another.

The new nerve then performs a new function. This can be challenging at first and may lead to some confusion. In fact, patients are recommended to undergo postsurgical physical therapy to retrain the nerve, a process called cortical remapping. In short, the nervous system needs to learn the new function of the nerve. Until then a patient might have difficulty controlling the affected area. As researchers at the School of Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis have explained, imagine using a nerve associated with breathing to fix a nerve in your arm and having to breath every time you flex.

Nerve transfers are sometimes used when the distance between the two healthy portions of a damaged nerve is too great for a successful nerve graft, or if one end of the damaged nerve no longer functions. They may also be used in more delicate areas, like the hands, as they’ve been shown to provide greater improvement when it comes to restored motor function.

When are nerve grafts necessary?

Traditional nerve grafts are all about bridging nerve gaps. They are primarily intended for peripheral nerve injuries that have left a space between functioning nerve ends. This sort of damage can be done through stretching, tearing, or severing of the nerve. Of course, as previously mentioned, there are other methods to repair damaged nerves as well.

While some nerves can repair themselves, the process isn’t always successful. Plus, nerves grow at an extremely slow rate (approximately one inch per month). This isn’t a problem for sensory nerves, but motor nerves are on a stricter timeline. If the nerve isn’t restored quickly enough, loss of muscle function will become permanent. Therefore, it’s that much more important to seek a surgical solution.

If the healthy nerve ends can be brought comfortably together, the nerve can be repaired without the help of grafts or nerve transplants. But if they can’t, or if bringing them together places stress on the nerve, a simple nerve repair won’t suffice. Peripheral nerve repair may also reveal the need for a nerve graft after the damaged portions of the nerve have been removed.

Nerve grafts are the standard procedure for nerve injuries that can’t be repaired directly. However, there is a limit to the length a nerve graft can reasonably become, and traditional nerve grafts require two functioning nerve ends. As mentioned earlier, this is when nerve transplants come into play.

The “graft to nowhere” is typically applied in cases of chronic pain. Because they’re not geared toward restoring movement or sensation, there’s no clear cutoff point for how soon the procedure needs to be performed.

Dr. Still tells the story of a patient who, after several foot surgeries, was left with chronic pain so debilitating that she struggled just to wear shoes. This pain had been going on for years when she finally came to Dr. Still. The nerve graft he performed left her without sensation in the top of her foot, or in other words, without pain.

>> If you suspect you have nerve damage or are experiencing chronic pain, reach out to our medical review team and get the needed help at the right time.

Which nerve is used for grafting?

There is no single best nerve for this role. Which donor nerve your surgeon chooses will depend on a variety of factors. In this section, we will outline many of these considerations and introduce some of the most popular donor nerves.

Donor Site Considerations:

- Importance of nerve role – The chosen graft should not provide any essential service. For example, a nerve that provides sensation to the side of the foot (sural nerve) is less essential than nerves in the hand or face.

- Ease of access to the nerve – As we mentioned earlier, nerves are so small that surgeons need microscopes to suture grafts in place. As such, it’s important that nerves are easy to access and remove.

- Nerve width and shape – Nerve grafts should be as much like the damaged nerve in size and shape as possible. Grafts that are too large or too small can lead to complications.

- Amount and organization of fascicles – Just as nerve grafts want to be similar in size and shape to the host nerve, so too do they want to have a comparable composition. Put simply, nerve grafts should have the same or similar number and organization of fascicles (nerve fiber bundles) as the damaged nerve. The more like the damaged nerve the graft is, the easier it will be for new nerve fibers to grow across it.

- Graft length – Certain donor grafts are capable of providing more graft material.

Popular Nerves for Grafting:

- Sural nerve – This sensory nerve runs down the back of the leg, providing sensation to the outer side of the foot. It’s a popular choice because of its size and less essential role in the overall nervous system. Graft lengths can reach 40 cm.

- Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve – This nerve resides in the inner arm and provides sensation to the inner arm, forearm, and elbow. It can provide a graft up to 20 centimeters in length. The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, located on the outer side of the arm, is also sometimes used. However, it can only provide a graft up to 8 centimeters and is an overall less popular choice.

- Superficial radial nerve – Also called the superficial radial sensory nerve or superficial branch of the radial nerve, this nerve runs along the forearm to the top of the wrist. This is a lesser used donor nerve but can come in handy when treating trauma to the radial nerve. Like the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, it can provide a somewhat longer graft (up to 20cm).

These few have been cited among the most common donor sites, particularly the sural nerve and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. However, there are several other nerves that may be chosen in specific situations. For example, the great auricular nerve, located just behind the ear, is actually very common for injuries to the trigeminal nerve (TN) in the temple.

What is a cable nerve graft?

Ideally, donor nerves will be as much like the injured nerve in size, shape, and composition as possible. However, it’s not always possible to get a perfect match. Still, surgery outcomes are greatly improved with closer matches.

Surgeons will sometimes combine segments of nerve to create a makeshift graft that is more suitable to the host site. For example, if the graft isn’t wide enough, the surgeon will place two or more lengths of graft side by side to more closely match the diameter of the damaged nerve. These are known as cable nerve grafts.

What is recovery from nerve grafts like?

The nerve graft recovery experience depends on the size and location of the graft. For example, larger grafts come with larger wounds, which take time to heal. Additionally, grafts in the extremities can severely limit movement during recovery.

Nerve graft recovery is not based on nerve regeneration. Long after nerve graft and donor site wounds heal, the nerve could still be regenerating. In fact, it can take years for a nerve to fully repair itself and for sensation to return.

On the bright side, you shouldn’t expect much of a hospital stay. Most nerve graft procedures are done on an outpatient basis. Note that we said, “most.” If your injuries are extensive, you may find yourself in a hospital bed after all.

You’ll be sent home with painkillers appropriate to your specific situation and dressings over the host and donor sites. If your graft is near a joint, then you may also have a splint in place to keep your joint from moving. This prevents tension on the graft, which can interfere with healing.

Follow all the postoperative bandage care guidelines given to you by your surgeon. Keep your bandages clean and dry, and don’t remove them unless instructed to do so. Additionally, you may be asked to perform certain exercises or undergo physical therapy. Physical therapy promotes strength and flexibility. In cases where motor nerves are being repaired, it can also help encourage new movement.

Expect numbness in both the host and donor sites. Over time your host site should regain all or most sensation as the nerve repairs itself. Remember that this is not the case with the “graft to nowhere,” which is intended to remove sensation. The donor site is another story. You’ve removed portions of nerve that were doing a specific job. As such, while numbness may decrease over time, it is unlikely to go away entirely. This is why nerves with less essential jobs are ideal for donor selection.

If the prospect of a permanent loss of sensation makes you uneasy, talk to your surgeon before undergoing the procedure. They may be able to provide you with a nerve blocker to give you some idea of what the loss of sensation will be like. This can be helpful when it comes to selecting the least intrusive donor site.

Surgery comes with general risks and complications. Keep an eye out for signs of infection and contact a doctor near you if you are concerned about your graft.

How successful are nerve grafts?

You have to decide what success means to you. If you expect a successful nerve graft to restore sensation and motion to pre-trauma levels, you’re probably going to be disappointed. As such, success is on a sliding scale. Talk to your surgeon about your unique prognosis and what they think might be capable with a nerve graft.

There are several factors that can influence the success of a graft.

- Size of injury – Larger grafts don’t heal as quickly or as well. Motor nerve grafts need to heal completely before loss of muscle function becomes permanent. The larger the graft – the less likely the nerve will heal in time.

- Quality of nerve preparation – Damaged nerves must be fully cleared of damaged material.

- Quality of graft – The more alike the damaged nerve and the donor graft, the better the outcomes. Additionally, both autografts and allografts should be sterile.

- Health of tissue – Healthy tissue on either end of a graft will help a graft revascularize more quickly. In other words, the blood supply will be restored to the graft tissue and the nerve fibers will start growing.

- Tension on graft – Tension after surgery can re-damage the nerve and interfere with the growth process.

While these are all important factors, the biggest when it comes to traditional nerve graft success is how long it’s been since the injury first occurred. The longer you wait to repair a nerve, the lower your chances of success will be. Of course, this doesn’t mean you need to rush through a graft surgery immediately after the injury. The likelihood of a successful graft starts to decline roughly 3 months post-injury.

If you think a nerve graft could be right for you, don’t be dissuaded by this sliding scale of success. Dr. Still encourages those experiencing chronic pain or other nerve problems to always consider nerve grafting as a possible option. Just make sure you understand what the graft is meant to accomplish. A big part of nerve graft success is going in to it with the reasonable expectations.